Introduction

There is a lot of buzz about lifelong learning and adults learning to code. While the reasons we hear tend to be quite logical and lucrative… they may feel tiring when we actually pursue it! It’s kind of like a rocket with a lot of fuel but may have too much drag friction. This blog article is about the benefits of using memory techniques with Anki, a learning tool. However, it provides a different line of reasoning; an emotional one that aims to remove some misconceptions that may hinder some of us. Ultimately, this article hopes to empower and energise you in your intellectual pursuits!

“Education is what survives when what has been learned has been forgotten.” - B.F. Skinner

It may be a bit ironic why logical people in technical fields need an emotional reasoning. From my experience, we may have some pre-conceived beliefs (from years of traditional study methods) that withhold us from reaching our goals. In any case, I’ve decided to include the logical argument as well because they are more concise.

What is spaced repetition and what is Anki?

“Spaced repetition is a centuries-old psychological technique for efficient memorisation & practice of skills where instead of attempting to memorise by ‘cramming’. Memorisation can be done far more efficiently by instead spacing out each review, with increasing durations as one learns the item, with the scheduling done by software (i.e. Anki).” - gwern.net

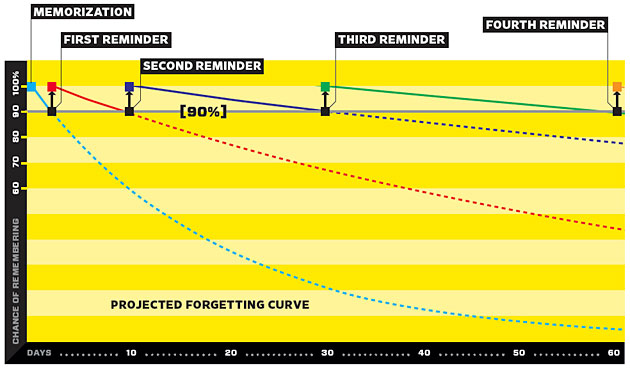

For example, you would learn an information and store it as a flashcard on day 0. Anki would notify and test you on day 1. If you get it correct, you will be notified and test you on day 3. If you get it correct again, it will notify you again and test you on day 7. This goes on and on at increasing durations. But if you get it wrong, you go back to day 0.

The effect is best illustrated in the graph above. With this slow and steady approach, it can scale the learner to memorise extremely large amounts of information.

It’s fairly simple. Still not convinved? Here are 3 myths that may be holding you back.

Myth 1: Memory/flashcards app is for medical students and translators. Engineers, physicists, mathematicians rely on intuition.

Emotional argument

An emotional argument is an argument that starts with something relatable.

We use Google search engine pretty much everyday. Be it finding a good restaurant with certain considerations or looking up StackOverflow for debugging answers. It seems that outsourcing our memory to an external storage is “good enough”. We can always look it up anyway. But this is sometimes misinterpreted into two sub-problems.

The first problem is that looking up still requires some pre-requisite information from us. In the Google example, we narrow our search result by adding keywords. Furthermore, we no longer have to learn from scratch if we are just referencing from online. The process of looking up would be a lot easier if our memory base is larger.

The second and deeper problem is that new innovative ideas often stem from long-term memory. Ideas can come from anywhere and having a large memory base allows for more interesting synthesis of disparate ideas from other disciplines.

Whether one is a problem-solving engineer or an innovative mathematician, memory isn’t the enemy. But rather, it is our friend that has silently helped us in our technical career.

Logical argument

I guess the most logical way to debunk this myth is to find counterexamples; reputable technical experts that use Anki. Michael Nielsen (Quantum computation physicist, author of popular deep learning book), Jeremy Howard (Machine learning researcher, fast.ai founder), and my economics professor are some examples and they all advocate the use of Anki in STEM education.

Myth 2: If it is important to you, you’ll remember it.

Emotional argument

I guess this myth came from a trope about some wife testing her husband: “do you remember our anniversary date?” The husband replies he doesn’t remember. And the wife says he doesn’t love her enough. The classic excuse by the husbands: there are too many things to remember!

The husband missed the purpose of this test. The wife may be asking for a proof of love but actually just wants to see the husband put in effort in the relationship. I think the wife would be okay if the husband revises with a notebook or has an early calendar entry.

I guess in some ways, this is why tech companies hiring practices usually involve a rigorous technical interview. It is not enough that the job is important to you, you need to put in the effort.

In essence, the causality is reversed. That is, we don’t automatically remember concepts that are important to us; we make the effort to remember things because anything important is worth putting in the effort.

Logical argument

According to science, this phenomena mostly applies to a type of memory called episodic memory. As for academic knowledge (i.e. “knowing” instead of “remembering”), it falls into another type of memory called semantic memory. Semantic memory improves with repetition whereas episodic memory degrades with repetition. (Learning and memory, 2016)

Myth 3: The effort-to-reward ratio is not worth it. My personal study techniques are more efficient.

Emotional argument

I understand that in some ways, I sound like we should all work as hard as medical students or graduate students. But really what I’m trying to say is that these people have learnt some efficient study techniques that I think it would be invaluable to the rest of us.

On the flipside, it may seem like the effort-to-reward ratio seems too good to be true (e.g. Singapore’s get rich gurus Dominic or Imran). No, I’m not asking you for anything; the article doesn’t even count to your medium.com article quota. The software is free and you can get started with your first flashcard in 5 minutes. There is very little effort in trying Anki!

Logical argument

A research review, titled What works, what doesn’t, compared various study techniques and found self-testing and distributed practice the top methods for learning. The bottom spot goes to rereading notes.

A harsher logical argument is that; hey, if you don’t have a second-upper honours (i.e. a GPA above 4.0/5), why not try a different study technique?

Conclusion

A personal tale

I first tried Anki in a biology course but unfortunately, I didn’t use the method properly and gave up in a week; before I could see any results. For the next 3 semesters, I’ve tried various study and productivity methods but they didn’t improve my grades either. I decided to come back to Anki after reading Michael Nielsen’s article and within 1 semester, it vastly improved my grades. I’m now a full-time software engineer but still use Anki everyday in various subjects.

Call for action

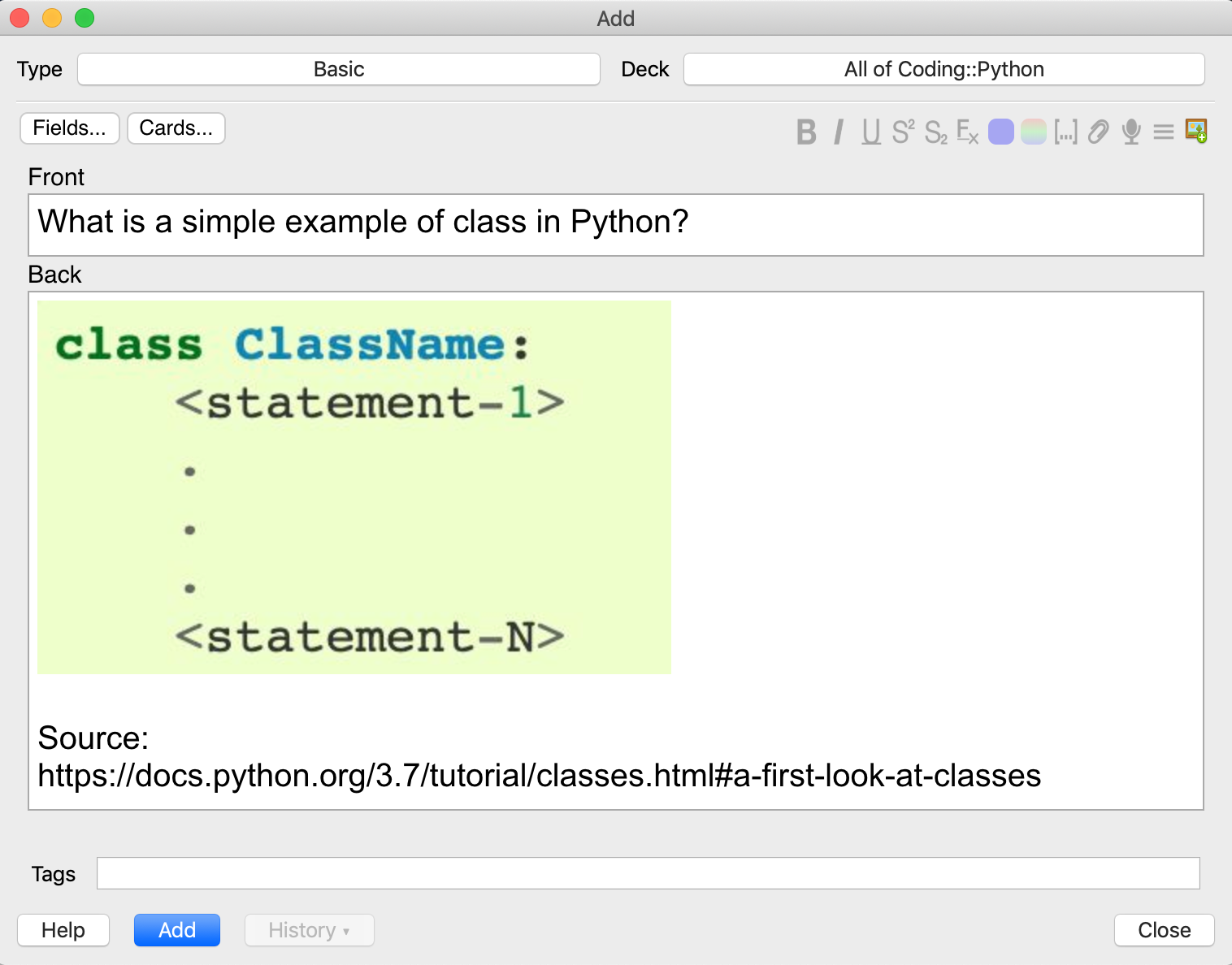

Start with short flashcards! Michael Nielsen started with bash command lines. I started with non-math subjects. The key to effective Anki cards is to make each card atomic. Here’s an example to get you started.

-

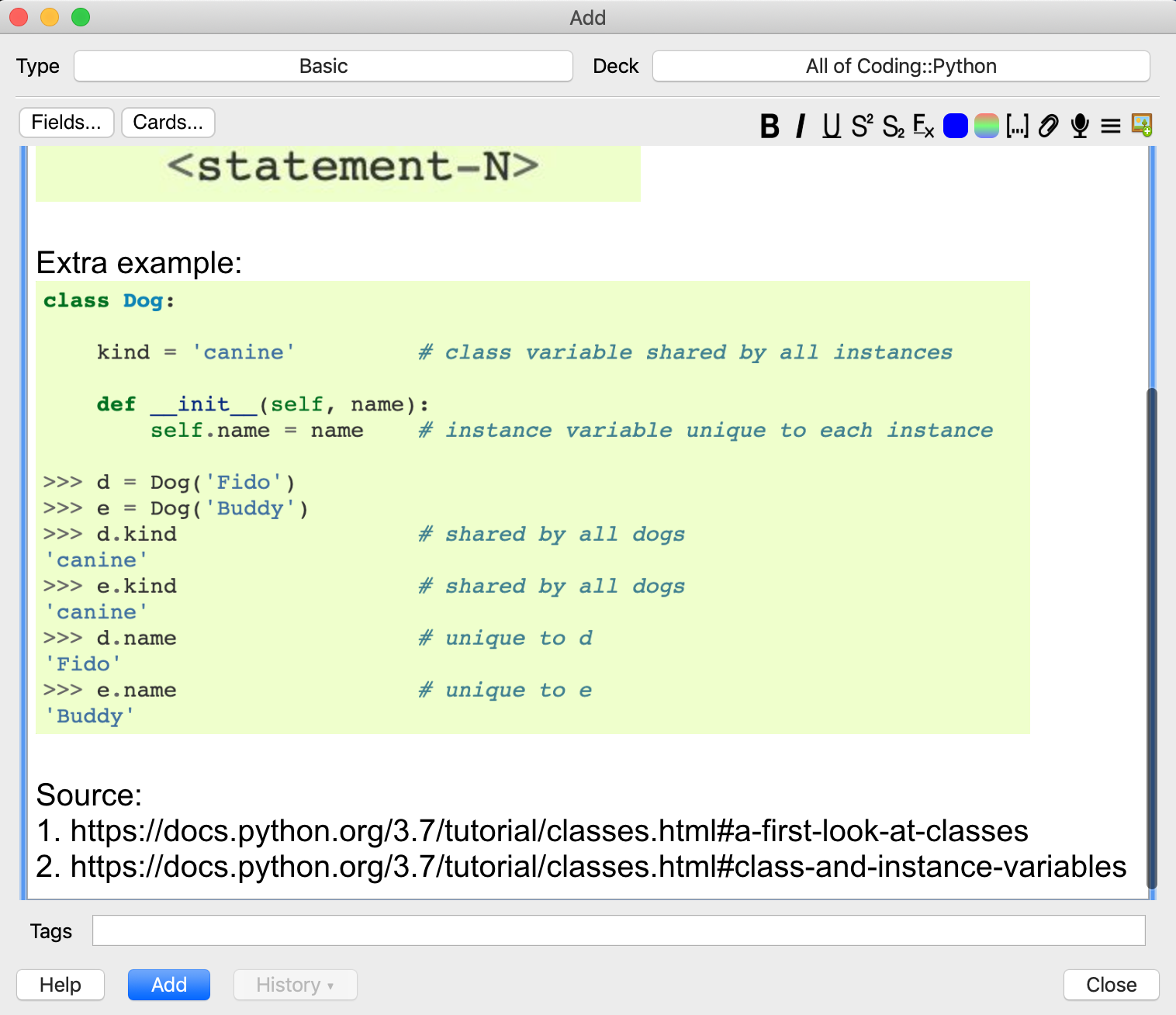

Pick a concept you want to learn. I’ve chosen Python’s

classsyntax. -

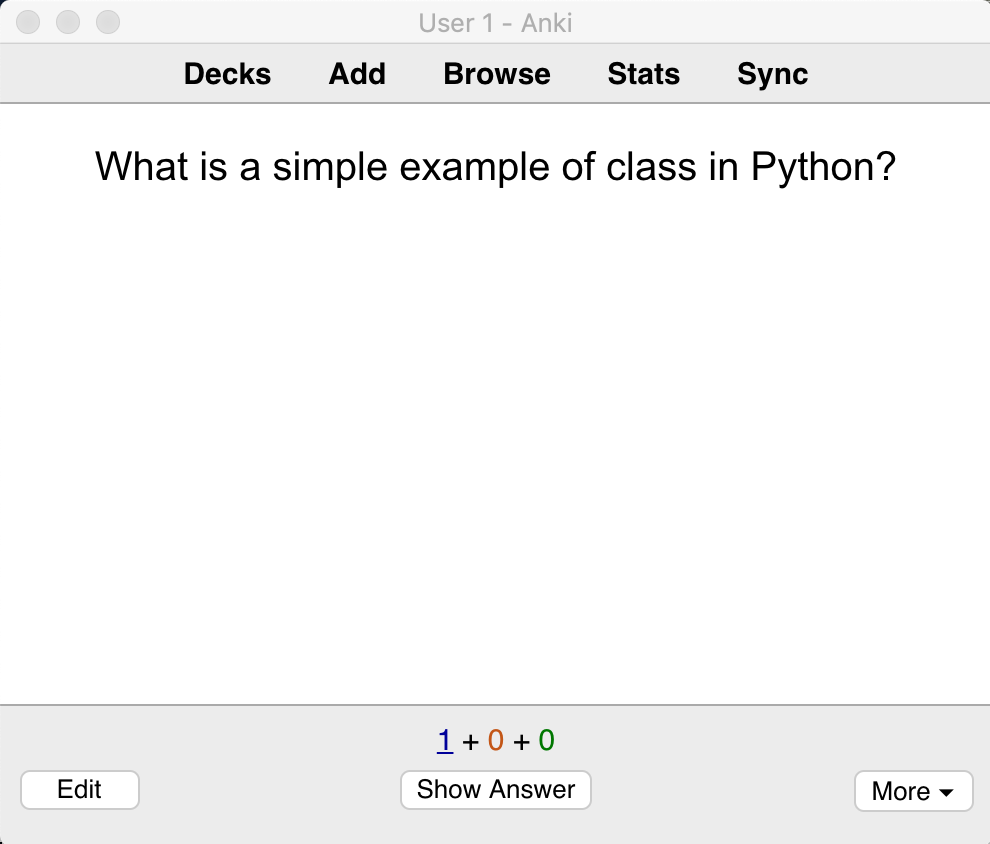

Write a question “What is a simple example of class in Python?” in the question box (front of flashcard). Copy-paste the screenshot from the official docs in the answer box (back of flashcard). Write the source.

3) I also recommend providing extra “bonus” examples but only if it helps in answering the simple example above!

4) Test yourself!

5) Click Good and revisit Anki the next day!

I’ve only scratched the surface on the “how” because I want to focus this article on the “why”. For more basic tips on making good flashcards, check out Derek Siver’s article!

If you’ve any questions or need help with Anki, you can contact me through email! :arrow_upper_left:

Helpful resources:

- Michael Nielsen’s Augmenting Long-term Memory.

- Chasing 10X: How Anki Saved My Software Career

- Derek Siver’s Memorizing a programming language using spaced repetition software

- iOS alternative: Cram app. The iOS version of Anki has a $25 fee but Cram seems like a good alternative.

“I’ve been doing this for a year, and it’s the most helpful learning technique I’ve found in 14 years of computer programming.” - Derek Sivers

References:

- Branwen, G. (2018). Spaced repetition. Retrieved from https://www.gwern.net/Spaced-repetition.

- Wolf, G. (2018, August 10). Want to Remember Everything You’ll Ever Learn? Surrender to This Algorithm. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/2008/04/ff-wozniak/.

- Gluck, M. A., Mercado, E., & Myers, C. E. (2016). Learning and memory: from brain to behavior. New York: Worth Publishers, Macmillan Learning.

- Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). What works, what doesn’t. scientific american mind, 24(4), 46-53.